Chords for Chord progressions explained on the piano

Tempo:

82.75 bpm

Chords used:

C

G

Fm

Eb

Bb

Tuning:Standard Tuning (EADGBE)Capo:+0fret

Jam Along & Learn...

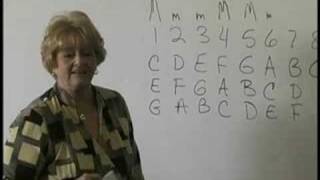

This video is about the way chord progressions work.

with my book, How To Really Play The Piano,

dealt with on pages 27 and 28.

What you do need to be able to understand is some basic stuff about chords and chord structures

If you're struggling with any of that stuff, then check out some of my videos on really basic harmony

or my videos on chord resolution.

on my video index page,

As I say, if you know all the basic stuff, then all of what follows should make perfect sense to you.

with my book, How To Really Play The Piano,

dealt with on pages 27 and 28.

What you do need to be able to understand is some basic stuff about chords and chord structures

If you're struggling with any of that stuff, then check out some of my videos on really basic harmony

or my videos on chord resolution.

on my video index page,

As I say, if you know all the basic stuff, then all of what follows should make perfect sense to you.

100% ➙ 83BPM

C

G

Fm

Eb

Bb

C

G

Fm

This video is about the way chord progressions work.

It's designed to tie in with my book, How To Really Play The Piano,

and if you're reading from the book, this is the material that you'll find dealt with on pages 27 and 28.

You don't need to be reading the book, however, to make sense of it.

What you do need to be able to understand is some basic stuff about chords and chord structures

and some basic terms such as tonic, subdominant and dominant.

If you're struggling with any of that stuff, then check out some of my videos on really basic harmony

or my videos on chord resolution.

You can find them all listed on my video index page,

the address of which you can find here. _

As I say, if you know all the basic stuff, then all of what follows should make perfect sense to you.

OK, so _ obviously different songs have different chord structures, different chord progressions or sequences,

and they all work in slightly different ways.

On the other hand, they do have things in common.

_ Now, what I'm going to talk to you about now isn't _ _ directly relevant to doing stuff like improvisation

or playing pop piano, but it's good background knowledge to have.

You'll find it comes in really handy if you ever try to start writing your own songs

or if you really find you're developing improvisations to a particularly intense degree.

_ _ The simplest way of thinking about any chord progression is in terms of it being a journey.

And that journey _ starts on the tonic chord, let's say we're in the key of C, so it would start on C,

and it journeys out away from C towards a [G] dominant chord, probably G, but it might be another chord that's like it,

it might be a quasi-dominant chord, like D minor 7 over G.

But the journey out very [C] basically goes from tonic to dominant, and the journey back goes from [C] dominant to tonic.

[Eb] Now, within any one chord progression, that journey might be repeated over and over again several times.

So if we think of a really, really very common chord sequence, _ E flat, [Cm] _

C minor [Fm] 7, F minor 7, [Bb] B flat 7,

_ you might know that from songs like, I think I've given it as an example [Eb] before, but songs like Blue Moon.

Blue Moon, you saw me standing alone, [Fm] without a dream in my heart, without [Eb] a love of my own.

And that's a really superb example of the principle.

We're travelling, we're starting on the tonic, which is E flat,

[Cm] going to a chord that's slightly different, _ C minor 7, [Fm] slightly different still, until we reach [Bb] our far furthest out point,

if you like, which is a dominant 7, B flat 7 in this case, and [Eb] then we return back to the tonic, and the sequence [Fm] starts again.

So we're travelling out to [Bb] the dominant, and [Eb] then back to the tonic.

OK.

Let's [Abm] think of another famous example.

_ [C] Let's look at when the Saints go marching in, in the key of C.

C, _ _ _ shouting out the chords here, C, _ still on C, to [G] G, the dominant, so we've gone from the tonic all [Em] the way out to the dominant,

[C] back to C, journey back, _ _ C7, [F] F, [Fm] F minor, _ _ [C] C, _ [G]

G, [C] dominant, C.

So as you can see, everything's happening around the tonic chord, which is called a C major, and we're going out and back, out and back.

Sometimes we're only getting as far as [Fm] F minor before coming back [C] to C, but most of [G] the time it's a very strongly dominant chord [C] like G.

OK.

As I say, if you look at most songs that you play, you know, if you have a few songbooks hanging around, look at the chord sequences.

It can be useful not to ignore the kind of, _ you know, the melody lines and the piano parts to them,

and just simply play through the chord sequence and get your head around the way different composers and writers construct chord sequences,

around that principle of starting on the tonic, moving away from it, but always coming back.

OK.

It usually goes via the dominant, or a chord that's like the dominant.

_ Of course, the tonic chord that the sequence comes back to can change.

That's a process known as modulation, where the whole key of a song changes.

Let me give you an example.

This is, if you're reading the book, this score I'm about to play is on the bottom of page 28,

and it's a very simple chord sequence that goes through C, A minor 7, F, G, but then modulates into the key of D flat,

so the tonic chord stops being C and starts being D flat.

OK, I'll play it through.

_ [G] _ _ [Em] _

_ _ [D] _ [F] _ _ _ [Em] _ _

[G] _ _ [Fm] There's the [Ab] modulation, _ [Db] and then we're into D flat.

_ _ You get the idea.

The way that's worked [C] is that we've been in the key of C where the dominant is G,

but as soon as the [Ab] chord of A flat appears, which is the dominant of D flat,

suddenly the sequence wants [Db] to start resolving back onto D flat [C] rather than C.

So that's modulation.

But basically, whatever the tonic chord is, the sequence will always try to come back to it.

And that's how chord sequences work.

No matter how complicated a piece of music is,

essentially all that's happening is a journey from the [G] tonic, away from the tonic, probably out to a dominant chord and back again.

And that might happen several times over the course of a chord sequence.

As I say, all kind of background theory information there, but useful stuff to know.

If you have any questions about any of that, please feel free to stick your question in the thread of the Jamcast post where this is posted.

You can find it here, it's the URL.

Or if you're watching on YouTube, by all means ask me a question in one of the YouTube comments.

If you're interested in finding out more about my book, How To Really Play The Piano,

The Stuff Your Teacher Never Taught You, here it is with the URL.

Basically it's a book aimed at people who have had some piano lessons,

but have got a bit bored of playing nothing but classics and scales and things,

and want to learn about jazz and blues and improvisation and playing pop and stuff like that.

You

It's designed to tie in with my book, How To Really Play The Piano,

and if you're reading from the book, this is the material that you'll find dealt with on pages 27 and 28.

You don't need to be reading the book, however, to make sense of it.

What you do need to be able to understand is some basic stuff about chords and chord structures

and some basic terms such as tonic, subdominant and dominant.

If you're struggling with any of that stuff, then check out some of my videos on really basic harmony

or my videos on chord resolution.

You can find them all listed on my video index page,

the address of which you can find here. _

As I say, if you know all the basic stuff, then all of what follows should make perfect sense to you.

OK, so _ obviously different songs have different chord structures, different chord progressions or sequences,

and they all work in slightly different ways.

On the other hand, they do have things in common.

_ Now, what I'm going to talk to you about now isn't _ _ directly relevant to doing stuff like improvisation

or playing pop piano, but it's good background knowledge to have.

You'll find it comes in really handy if you ever try to start writing your own songs

or if you really find you're developing improvisations to a particularly intense degree.

_ _ The simplest way of thinking about any chord progression is in terms of it being a journey.

And that journey _ starts on the tonic chord, let's say we're in the key of C, so it would start on C,

and it journeys out away from C towards a [G] dominant chord, probably G, but it might be another chord that's like it,

it might be a quasi-dominant chord, like D minor 7 over G.

But the journey out very [C] basically goes from tonic to dominant, and the journey back goes from [C] dominant to tonic.

[Eb] Now, within any one chord progression, that journey might be repeated over and over again several times.

So if we think of a really, really very common chord sequence, _ E flat, [Cm] _

C minor [Fm] 7, F minor 7, [Bb] B flat 7,

_ you might know that from songs like, I think I've given it as an example [Eb] before, but songs like Blue Moon.

Blue Moon, you saw me standing alone, [Fm] without a dream in my heart, without [Eb] a love of my own.

And that's a really superb example of the principle.

We're travelling, we're starting on the tonic, which is E flat,

[Cm] going to a chord that's slightly different, _ C minor 7, [Fm] slightly different still, until we reach [Bb] our far furthest out point,

if you like, which is a dominant 7, B flat 7 in this case, and [Eb] then we return back to the tonic, and the sequence [Fm] starts again.

So we're travelling out to [Bb] the dominant, and [Eb] then back to the tonic.

OK.

Let's [Abm] think of another famous example.

_ [C] Let's look at when the Saints go marching in, in the key of C.

C, _ _ _ shouting out the chords here, C, _ still on C, to [G] G, the dominant, so we've gone from the tonic all [Em] the way out to the dominant,

[C] back to C, journey back, _ _ C7, [F] F, [Fm] F minor, _ _ [C] C, _ [G]

G, [C] dominant, C.

So as you can see, everything's happening around the tonic chord, which is called a C major, and we're going out and back, out and back.

Sometimes we're only getting as far as [Fm] F minor before coming back [C] to C, but most of [G] the time it's a very strongly dominant chord [C] like G.

OK.

As I say, if you look at most songs that you play, you know, if you have a few songbooks hanging around, look at the chord sequences.

It can be useful not to ignore the kind of, _ you know, the melody lines and the piano parts to them,

and just simply play through the chord sequence and get your head around the way different composers and writers construct chord sequences,

around that principle of starting on the tonic, moving away from it, but always coming back.

OK.

It usually goes via the dominant, or a chord that's like the dominant.

_ Of course, the tonic chord that the sequence comes back to can change.

That's a process known as modulation, where the whole key of a song changes.

Let me give you an example.

This is, if you're reading the book, this score I'm about to play is on the bottom of page 28,

and it's a very simple chord sequence that goes through C, A minor 7, F, G, but then modulates into the key of D flat,

so the tonic chord stops being C and starts being D flat.

OK, I'll play it through.

_ [G] _ _ [Em] _

_ _ [D] _ [F] _ _ _ [Em] _ _

[G] _ _ [Fm] There's the [Ab] modulation, _ [Db] and then we're into D flat.

_ _ You get the idea.

The way that's worked [C] is that we've been in the key of C where the dominant is G,

but as soon as the [Ab] chord of A flat appears, which is the dominant of D flat,

suddenly the sequence wants [Db] to start resolving back onto D flat [C] rather than C.

So that's modulation.

But basically, whatever the tonic chord is, the sequence will always try to come back to it.

And that's how chord sequences work.

No matter how complicated a piece of music is,

essentially all that's happening is a journey from the [G] tonic, away from the tonic, probably out to a dominant chord and back again.

And that might happen several times over the course of a chord sequence.

As I say, all kind of background theory information there, but useful stuff to know.

If you have any questions about any of that, please feel free to stick your question in the thread of the Jamcast post where this is posted.

You can find it here, it's the URL.

Or if you're watching on YouTube, by all means ask me a question in one of the YouTube comments.

If you're interested in finding out more about my book, How To Really Play The Piano,

The Stuff Your Teacher Never Taught You, here it is with the URL.

Basically it's a book aimed at people who have had some piano lessons,

but have got a bit bored of playing nothing but classics and scales and things,

and want to learn about jazz and blues and improvisation and playing pop and stuff like that.

You